Does the Experimenter's Handedness Influence an Infant's Hand Preference for Grasping?

In this paper we investigated the effect of the experimenter’s handedness on infants’ choice of what hand to use in a handedness test. We divided forty-eight 12- month-old infants into four groups, depending on the experimenter’s handedness (right-handed or left-handed) and the condition (experimenter writing or not writing). The results show that when the experimenter wrote, the infants were significantly less likely to use their right hand alone to grasp objects than infants in the no writing condition, resulting in a significantly lower handedness index. However, the effect on handedness index was the same independently of the experimenter’s handedness. These results are discussed in terms of attentional factors and motor resonance influencing infants’ choice of hand during a handedness test. Handedness has been shown to start as early as in utero, when fetuses suck their right thumb more than their left at 15 weeks of gestation. Although this early manual lateralization seems to be predictive of later handedness, the age at which infants’ handedness is comparable to that of adults remains unclear. As soon as infants start grasping objects, most do so more with their right hand than with their left. However, the percentage of non-lateralized infants is often found to be larger than the percentage of left- and even of right-handers, in any case much larger than in adults. Moreover, at the individual level, handedness goes through many fluctuations during the first months of grasping at least in the majority of infants. If handedness is neither strong nor stable in early childhood, it should be particularly sensitive to factors influencing its manifestation, such as spatial configuration, object size, experimenter’s handedness, etc. The hand used for object grasping has indeed been shown to be very sensitive to object and task characteristics, such as precision grip, object size and object spatial position. The goal of the study presented here was to study the influence of another factor likely to affect the infant’s choice of hand to grasp an object during a handedness test: namely, the experimenter’s own handedness.

Forty-eight infants were tested in our baby lab. They were 12- months-old (Mean=368 days [Range: 352-384]; 24 girls). The infants had been born full-term and were free of neurological disorders. Parental consent was granted before observing the infants. We also recorded parents’ handedness. All children were given a classical handedness test. The baby handedness test (BbHtest) comprises 15 items. The objects used were small baby toys, between 0.5 and 7 cm wide and between 2 and 17 cm high. We avoided objects inviting bimanual manipulation, such as objects with a separately mobile part, since in this case, the infant may grasp the object with the non-preferred hand in anticipation of using the preferred hand for the more active part of the action. The order of presentation was random. All objects were presented on the table along the midline within reaching distance of the infant, and handed to the infant by the experimenter using her two hands. After a few minutes, the experimenter used her two hands to gently take the object from the infant, and the next object was presented. All infants were tested in the same room in our babylab, and were seated on their parents’ lap during the whole test session, which lasted no more than 15 minutes. A videocamera recorded all sessions. We checked the possible effect of the experimenter’s use of her preferred hand to tick off the infant’s response on a sheet of paper after each object presentation.

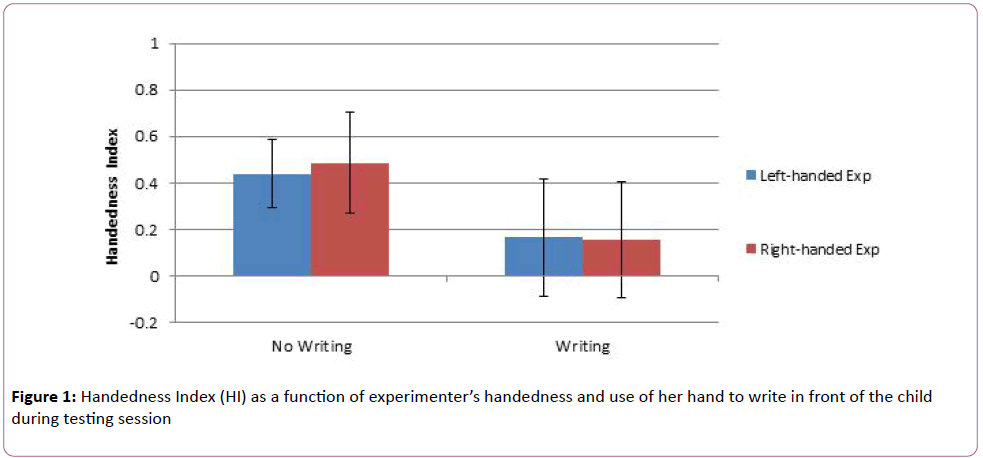

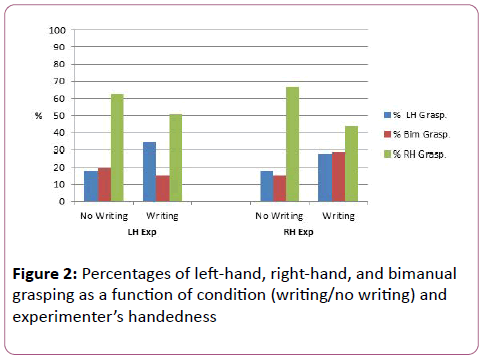

As shown in Figure 1, the infants showed much less right-handedness in grasping the object in the writing than in the no writing condition. The unexpected result was that infants in the writing condition showed less right-handedness regardless of which hand the experimenter used to write. An ANOVA calculated on HI as a function of experimenter’s handedness (right-handed vs. lefthanded) and condition (writing vs. no writing) indicated a significant effect of condition, F(1,44)=5.72, p=0.021; Cohen’s d=0.71, but no effect of experimenter’s handedness, p=0.88, and no Condition x Experimenter’s Handedness interaction, p=0.83. Thus, whatever hand the experimenter used to write, the infants in this condition showed a lower percentage of righthand grasping compared to the no writing condition.

In conclusion, observing the experimenter writing during the session decreases infants’ expression of right-handedness. Part of the effect may reflect some motor resonance, but attentional factors might be equally important. Further studies with more infants are needed to tease apart the respective influence of the experimenter’s handedness (anatomical vs. spatial motor resonance) and of attentional bias in infants’ hand choice for grasping.

For more info kindly visit our Journal page: https://www.imedpub.com/brain-behaviour-and-cognitive-sciences/

With Regards,

Joseph Kent

Journal Manager

Journal of Brain Behaviour & Cognitive Sciences